O5. Inhaler technique and adherence

Jump to

O5.1 Inhaler technique

Incorrect inhaler technique is common and is associated with worse outcomes. A systematic review of articles reporting direct observation of inhaler technique in COPD and asthma reported that the overall prevalence of optimal inhaler technique was only 31% (95% CI 28 to 35%), and that this pattern had not improved over 40 years. Common errors were identified, for the MDI these were poor coordination (45%; 95% CI 41 to 49%), inadequate speed and/or depth of inspiration (44%; 95% CI 40 to 47%), and the absence of post inhalation breath-hold (46%; 95% CI 42 to 49%). For the DPI, common errors included incorrect preparation in 29% (95% CI 26 to 33%), inadequate expiration before inhalation in 46% (95% CI 42 to 50%), and the absence of a post inhalation breath-hold in 37% (95% CI 33 to 40%) (Sanchis 2016). These data highlight the importance of inhalation technique education.

Inhaler devices must be explained and demonstrated for patients to achieve optimal benefit. It is necessary to check regularly that the patient has the correct inhaler technique as proficiency will wane with time. Ensuing that patients are shown the correct inhaler technique requires the health professional to have an understanding of the devices. Unfortunately, large gaps remain in health professionals’ knowledge and skill in this area. A systematic review that included 55 studies and evaluated health professionals performing 9,996 tests demonstrating their inhaler technique confirmed this (Plaza 2018) [evidence level I]. Inhaler technique was only considered correct in 15.5% of health professionals (95% CI 12 to 19.3) overall. Another finding of the review was that inhaler technique proficiency of health professionals has decreased over time. In studies between 1975 and 1995, overall proficiency was 20.5% (95% CI 14.9 to 26.8) compared to only 10.8% (95% CI 7.3 to 14.8) in the period between 1996 and 2014. These data highlight the necessity of health professionals to develop their knowledge and proficiency of inhaler device use.

Elderly and frail patients, especially those with cognitive deficits, may have difficulty with some devices. Correct inhaler technique is essential for the optimal use of all inhaled medications (Melani 2011) [evidence level I] and is associated with fewer severe exacerbations. An observational study involving 2,935 patients with COPD, reported that in individuals who were treated for at least three months (n=2,760), the occurrence of prior (past three months) severe exacerbation was significantly associated with at least one observed critical error using prescribed inhalers (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.14-3.04; p=0.0053) (Molimard 2017). Ease of operating and dose preparation were rated as being the most important inhaler features leading to higher patient satisfaction and fewer critical errors in a randomised, open-label, multicentre, cross-over study of two inhaler devices (van der Palen 2013) [evidence level II]. An Australian cross-sectional study found that the proportion of patients with COPD who made at least one error in inhaler technique ranged from 50 to 83%, depending on the device used (Sriram 2016). Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 72 studies involving asthma and COPD patients, reported that 50-100% of patients performed at least one handling error. The pooled summary results for pMDI estimated an overall error rate of 86.6% (95% CI 79.4-91.9) and for DPIs it was 60.9% (95% CI 39.3-79.0) (Chrystyn 2017) [evidence level I].

Consideration of cognitive impairment is important for the learning and retaining of inhaler technique (Baird 2017, Iamthanaporn 2023) [evidence level I]. Ongoing training for re-enforcement, or alternative inhaler device substitution, may be beneficial.

With the proliferation of new inhaler devices, inhaler device poly-pharmacy is becoming an increasing problem amongst COPD patients and has a negative impact on outcomes (Bosnic-Anticevich 2017) A study of 16,450 COPD patients compared exacerbation frequency and SABA use of patients who were using similar style inhalers e.g. all MDI to those that were prescribed devices that required a different technique. Those in the similar device cohort experienced fewer exacerbations (adjusted IRR 0.82, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.84; and used less SABA (adjusted OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.51-0.57), compared to the mixed device cohort. Adherence may also be improved when using single inhaler therapy compared to multiple inhaler therapies. A GSK-led retrospective study using a large US claims database involving 9942 patients demonstrated that those who initiated triple therapy with single-inhaler fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol (FF/UMEC/VI) had significantly better adherence (46.5% vs. 22.3%; RR 2.08, 95% CI 1.85–2.30) and persistence (35.7% vs. 13.9%; HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.81–2.01, p<0.001) compared with patients who initiated multiple inhaler therapy (Mannino 2022) [evidence level III-2]. These data support the recommendation to minimise the number of different devices prescribed in COPD patients. Single combination inhaler devices have comparable efficacy to multiple inhaler devices, delivering the same medications and doses without any additional safety concerns. Retrospective and prospective studies have shown that using a single inhaler was associated with decreased healthcare resource utilisation and improved cost-effectiveness compared with multiple inhalers. However, due to the lack of long-term data, differences in outcome definitions and study designs, robust conclusions regarding the differences between single- and multiple inhaler users cannot be made (Zhang 2020) [evidence level I].

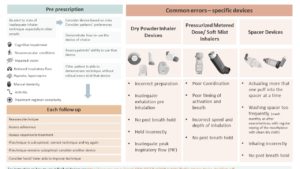

An infographic highlighting important considerations for in haler device prescription is included below.

Figure 5: Important considerations for inhaler device prescription

Content has been reproduced with permission from the Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits, originally developed as part of the Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits (https://treatabletraits.org.au) in collaboration with the COPD-X Guidelines Committee.

Lung Foundation Australia has developed a series of inhaler device technique videos and factsheets for patients which provide step-by-step instructions on correct inhaler technique. These and other resources are available at:

-

- https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/?user_category=32&search=inhaler%20device.

- NPS Medicine Wise has also developed a checklist for inhaler device technique available at https://www.nps.org.au/assets/NPS-MedicineWise-Inhaler-Technique-v2-jg-120320-ACC.pdf

- The National Asthma Council has produced a number of “how-to” videos which are available on their website at https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/how-to-videos.

- The Lung Foundation Australia resource, Better Living With COPD: A Patient Guide contains an inhalation devices chapter. This patient guide can be accessed at https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/better-living-with-copd-booklet/

The cost of inhaler devices varies between products. As there are no differences in patient outcomes for the different devices, the cheapest device the patient can use adequately should be prescribed as first line treatment (NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2003). The range of devices currently available, the products and dosage, as well as their advantages or disadvantages, are listed in Appendix 2. Brief counselling; monitoring and feedback about inhaler use through electronic medication delivery devices; and multi-component interventions consisting of self-management and care co-ordination delivered by pharmacists and primary care teams have been shown to improve medication adherence (Bryant 2013) [evidence level I].

Pharmacist-led interventions comprising information provision, motivating patients and taught necessary behavioural skills significantly improved medication adherence (1.41 [1.24 to 1.61], P < .00001) and correct inhalation technique (Risk Ratio 1.85, 95% CI 1.57 to 2.17), compared with the control group (Jia 2020) [evidence level I].

O5.2 Inhaler adherence

Bhattarai et al (2020) conducted a systematic review of 38 studies published from 2003 to 2019 that examined rates of medication adherence and reported on barriers and enablers to adherence. Rates of non-adherence ranged from 22% to 93%. The majority of studies identified the presence of depression and subjects’ concern about the harmful effects of the medicine as barriers to adherence (Bhattarai 2020).

A systematic review comprising predominantly retrospective database studies which measured prescription refill adherence with one-to-two-year follow-up of patients with COPD found increased hospitalizations, mortality, poor quality of life and loss of productivity among non-adherent patients (van Boven 2014) [evidence level III-2]. Inhaler adherence and technique were found to be suboptimal in an observational study of use of an ICS/LABA combination inhaler fitted with an electronic audio recording device. Impaired lung function and cognition, as well as cough, predicted suboptimal adherence and technique (Sulaiman 2017).

A large retrospective study examined medication use data of patients with asthma and COPD from a digital health platform (smartphone application [mobile app] and electronic medication monitors). They compared adherence rates using a once daily controller regimen compared to twice daily. In 1791 patients with COPD, once daily was associated with higher median daily adherence than the twice daily regime 83.3% [IQR: 57.2 to 95.6] versus 64.7% [IQR: 32.8 to 88.9], p < .001). In COPD once daily regimen was also associated with an increased odds of achieving ≥80% adherence [1.73 (95% CI: 1.38-2.17, p < .001)]. Patients received electronic reminders via a mobile app if the medication was not taken, therefore inflating real life adherence rates. These data highlight the importance of identifying the regimen most likely to lead to improved adherence (De Keyser 2023) [evidence level III-I].

A systematic review of 26 studies involving people with asthma and COPD, seven were COPD specific. The aim of the review was to examine the cost consequences, cost-effectiveness, and budget impact of interventions that were designed to improve adherence to inhaled medications in asthma or COPD. The authors reported that interventions promoting adherence mostly had a positive impact on cost, and often resulted in reduced health care utilisation (vanBoven 2024) [evidence level I].

The National Asthma Council of Australia’s Australian Asthma Management Handbook contains further information about adherence: http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/management/adherence.

< Prev Next >